|

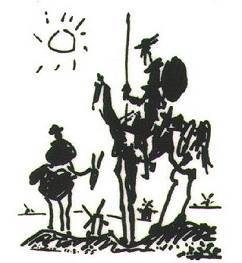

FLY CASTING WITH THE

MAN OF LA MANCHA

by Randy Kadish

The sunlight shined through

the blinds. Time for me to get out of bed. I tried, sort of, but

felt weighed down, as if I were a knight, fallen, encased in heavy

armor. Was I defeated?

I pulled the sheets over my

head and hoped the new year, 2007, would bring sales of my book, and

money so I could finally travel to faraway fishing destinations. But

2006 started with so much hope. What did it bring?

I thought of the vision test

I failed, ending my hopes of becoming a court officer. I thought of

all the mistakes in the first printing of my book - the proofreader

had fallen down on the job - forcing me to have the book reprinted,

at my expense. Two major disappointments. Two major reversals. Was I

being punished - trampled on like the knight Don Quixote - for

dreaming of doing good? If only the Man of La Mancha had succeeded

in making the world a fairer place, then I'd be standing victorious.

Wouldn't I?

I thought of the magazines

that bought my stories but, for different reasons, didn't publish

their next issues.

I thought of my two new

jobs.

Three more disappointments,

five so far for the year. More than in most novels. And I still

wasn't in the final crisis.

I thought of the GLX fly rod

I lost. I thought of the woman from the army.

Seven disappointments, not

quite as many as Don Quixote, but Don wasn't real. Maybe that's why

he never had trouble getting out of - or even into - bed. Real or

not, I wanted to be more like the Don. Besides, the weather was

unusually mild, as if I were in southern Spain. A plus. An

opportunity to fish and write myself a better plot-line.

Lighthouse

Park

I rolled out of bed, ready

to battle with striped bass. Instead of armor, I took my fly-fishing

equipment and headed out the door. Less than an hour later I walked

to the north end of Roosevelt Island, and into a scene as beautiful

as any in La Mancha. I was in Lighthouse Park. The small park was

named after a tall, narrow, stone structure that I knew was not an

evil giant. I rolled out of bed, ready

to battle with striped bass. Instead of armor, I took my fly-fishing

equipment and headed out the door. Less than an hour later I walked

to the north end of Roosevelt Island, and into a scene as beautiful

as any in La Mancha. I was in Lighthouse Park. The small park was

named after a tall, narrow, stone structure that I knew was not an

evil giant.

I didn't attack.

Roosevelt Island was about

two miles long, and a hundred yards wide. It split the East River -

a major migratory route for stripers - in half. North of the island,

the river again split, this time around Randall's Island. Half of

the river turned eastward, flowed under the Triboro Bridge - a

bridge connecting three counties of New York City - and merged with

the Long Island Sound. The other half of the river hooked westward,

then straightened and flowed out of my view and eventually, I knew,

merged with the Hudson River.

I looked west, across the

river, and saw about a half-mile of the Manhattan skyline. Most of

the buildings were built in the nineteen-fifties and sixties, eras

when New York architects were concerned with cost and function, so

though few of the buildings were beautiful, they merged, like bodies

of water, and formed a skyline whose whole was greater than its

parts. A plus, in my book.

I turned, looked east and

saw an ugly Queens housing project. A minus. Unlike the different

shaped and sized buildings of the Manhattan skyline, all the

project's brick buildings were cross-shaped and seven-storied. I

wished I could be a real Don Quixote and obliterate them. But

obliterating them wouldn't be easy, especially because they suddenly

looked like giant soldiers - maybe from outer space - all wearing

the same uniforms and standing in perfect formation.

Were they planning an

attack, perhaps against the high-income buildings of the Manhattan

skyline? Was I standing on another world's - perhaps a parallel

universe's - battle line? Would the rules of the Geneva Convention

apply?

They wouldn't have to. The

housing project, I remembered, was home to many people. No matter

how ugly it was, I didn't want to see it go.

I set up my fly rod and tied

on a white and green deceiver. The wind, not strong but steady, blew

from the west. To cut through it, I'd have cast straight back.

Still, I was confident I'd again cast over a hundred feet. I faced

the housing project and false cast, shooting more and more line. But

my casts sagged. My loops opened wide. What was I doing wrong? Or

was I, like the pirated Don Quixote, just in a bad sequel? If so, I

wanted out, or at least a casting coach, a Sancho Panza so to speak,

to keep my casting on the straight and narrow.

I told myself I shouldn't

have stopped practicing long-distance fly casting. After all, Don

Quixote, up until his very end, didn't get burned out. Why? Because

he had his impossible dream? Didn't I: to become a consistent

100-foot fly caster, and to write casting articles and help other

anglers?

I accelerated my cast, then

abruptly stopped it and let go of the line. My deceiver landed only

about eighty-feet away. Disappointed, I quickly retrieved. Again I

false cast. Again my casts sagged. I cursed. Why, I wondered, after

years of casting tribulations, after finally coming to believe I

fixed my casting defects, does a new one confront me like a villain?

Is this another reversal? Another obstacle? But obstacles are meant

to be overcome. Just ask Don Quixote.

I thought back to the first

act of my fly-casting adventures: I tried to decipher fly-casting

book after book, then I marched to a lawn and practiced casting, day

after day.

I thought back to the second

act: I tried to cast farther than 80 feet. But the fly often hit me.

An unexpected reversal. Why? I reread my fly-casting books and

learned that I was lowering my rod hand at the end of the cast, and

therefore pulling down the fly line. I returned to the lawn, and

though I tried not to, I still lowered my rod hand. So four times a

week, month after month, I experimented with every part of my

cast--stance, trajectory, follow-through--but the fly still hit me.

Darn it! Downtrodden, feeling I was at a dead-end, I trudged home,

thinking of how foolish Don Quixote was for trying to change the

world, and how foolish I was for thinking I could become a 100-foot

fly caster.

And so I wrote another

failure into the story line of my life. A few weeks later, this new

failure began to chomp away at me, at my self-worth, so I got back

on my fly-casting horse and resumed practicing. Then by accident,

like a contrived ending, I realized that when I cast with my elbow

pointed all the way out, my rod hand moved downward and pulled down

the fly line.

Thrilled with my new

discovery, I cast back and forth and watched my long loops tighten

and streak like arrows.

During the next few months I

overcame other fly-casting obstacles, and finally I cast a hundred

feet! I reached my impossible dream - for a while anyway, because as

I fished on Roosevelt Island I realized dreams, or at least some of

them, are fleeting.

Roosevelt Island

Seagulls dived in the East

River. Bait fish! Maybe Stripers were chasing them. I cast toward

the birds. Again my line sagged. I couldn't reach my target. I

cursed, then remembered I wasn't in a real-life tragedy, though,

like Don Quixote, I was in publications, including my long-distance

fly-casting article. Maybe it held a forgotten solution to my

casting defect. And if not - well, I still had faith the new

obstacle was something I could overcome. So instead of feeling

defeated, I enjoyed fishing and feeling connected, like a bridge, to

the beauty all around me.

Four hours later, as soon as

I got home, I started rereading my casting article. About a third of

the way through, I read that if my back cast and forward cast formed

an angle greater than 180 degrees I probably stopped the rod too

late, after it started unloading and losing power. If I back cast

parallel to the ground, therefore, I had to forward cast with the

same or slightly higher trajectory.

I rediscovered my solution!

My story had a good ending.

Grateful, I closed my eyes

and wondered why casting ten or twenty feet farther was so important

to me. Were my casting experiments about more than distance?

Yes, they were also about

coming to believe in an ideal casting form, as absolute as a perfect

literary form, like Shakespeare's 29th or 30th sonnet, as absolute

as a law of physics, like Special Relativity. But why is, why was

that so, so important? Is it because even though the world is

riddled by random turns of history and bloodied by wars, the world,

or at least our solar system, is also unified by ideals that form a

working order? If so, are ideals invisible and so hard to discover

for a reason - so I can't invent them in the universe of mind? Why?

Is it because what gives ideals meaning is the search for them, the

attempt to become in-line with them and then be able to overcome my

defects, my obstacles and to connect to the good in the world?

Isn't that what spirituality

is about? Perhaps an ideal, therefore, is a part that can never add

up to a whole. And perhaps so am I. That's why when I tried to will

things my way I almost always fell off my horse and cursed a world

that seemed so unjust.

But that was then. This is

now, and now I'm able to deal with disappointments, one by one, and

keep going, like Don Quixote, and to keep believing that there is a

working order of things.

Yes, I believe by the end of

the book of my life, the good will outweigh the bad. Randy's

historical novel, The Fly Caster Who Tried to Make Peace with the

World, is available on Amazon.

Text and photos by Randy Kadish 2007 ©

Randy's historical novel,

The Fly Caster Who Tried To Make

Peace With The World, is available on

Amazon. |